All You Need To Know About Cookie Consent On Your Website

In This Article

As online shopping, social media, and new initiatives in tech—like the metaverse—become increasingly prevalent for businesses and advertisers, many governments are taking measures to protect consumer data. In 2016, the European Union launched its General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) guidelines. This initiative aims to protect consumer data through federal regulation, including a crackdown on consumer data tracking: “No communications should be subject to unlawful tracking and monitoring without freely given consent, whether by cookies, device-fingerprinting, or other technological means.”

In 2020, California adopted measures similar to the GDPR, and on January 1, 2023, the state of Virginia implemented almost identical regulations. These laws include the rights below for consumers (taken from The California Consumer Privacy Act—CCPA and The Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act—VCDPA):

- Know the personal information a company collects about consumers and how it is used and shared.

- Obtain copies of the personal data collected by the business for third-party.

- Delete personal information they have given to businesses.

- Opt out of sharing their personal information.

Although consumer data privacy in the U.S. is most prevalent in California and Virginia, having GDPR-compliant cookie practices on corporate websites is becoming standard for two reasons:

- We live in a connected world of e-commerce. Businesses cannot predict where their consumers are browsing from. Being GDPR-compliant ensures your website isn’t breaking the law in any country.

- Because the standard of opt-in cookie compliance is becoming common, consumers are starting to expect it. So, when they visit a website and don’t see a notice about cookie tracking, they may not trust that company with their data or worry that they’re being tracked without their consent.

As a company, understanding cookie consent and how it impacts your website’s user experience (UX) is critical both from a legal and marketing strategy standpoint.

What Are Cookies?

Cookies are tools stored within browsers that track a user’s experience online. Cookies can track which websites users visit and how frequently they visit them. They can also track a user’s behavior on an individual website, such as the time spent on a page, clicks to another page, purchases, video views, and more. Marketers can use these kinds of cookies to determine how to serve a user different kinds of content based on their browsing history.

One of the most practical kinds of cookies for most consumers is the kind that stores a visitor’s browsing preferences for a specific website—including saving login information. When you clear cookies like these, you have to re-enter that login information when returning to the website.

What’s the Difference Between First-Party Cookies and Third-Party Cookies?

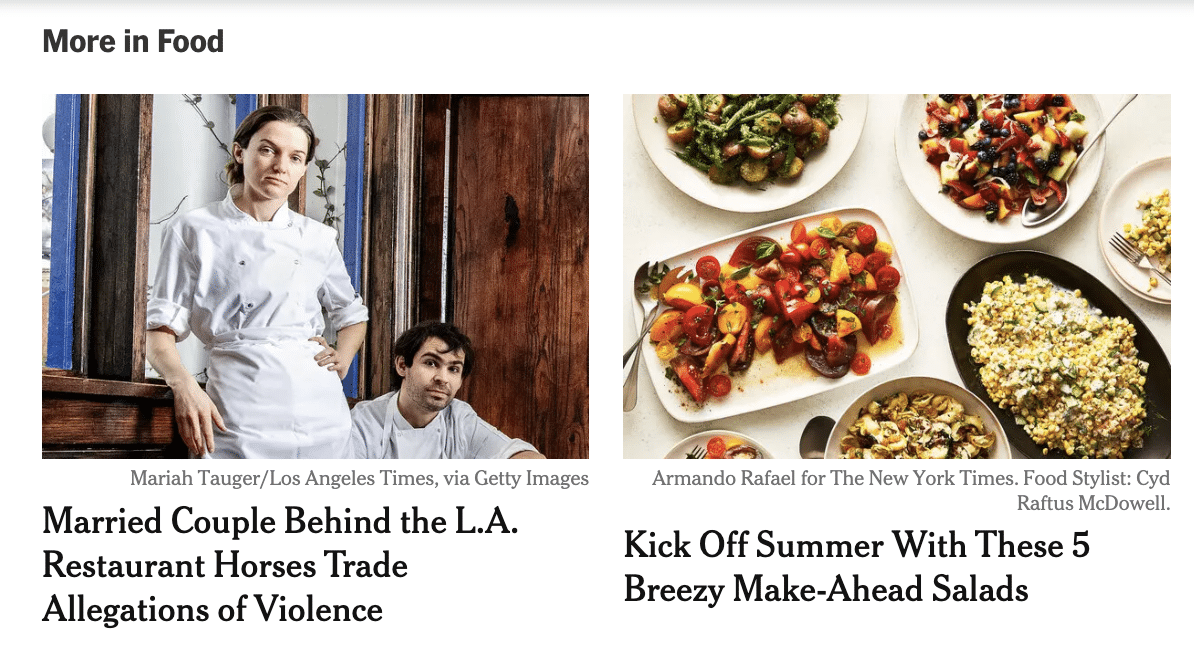

First-party cookies are stored on individual websites. You likely have a login account if you subscribe to The New York Times and like browsing their stories online. The New York Times’ first-party cookies can store your password and track what topics you like to read about to give you a better reading experience.

For example, if you primarily follow cooking and recipes and have opted into first-party cookies, you’ll see other cooking-related New York Times articles show up in the sidebars and footers of the articles you read (example below):

Third-party cookies are created by marketing and advertising services to target consumers outside of their organic browsing experiences. These cookies collect data across multiple websites and then show users ads based on where they’ve been online.

Third-party cookies often make users feel like a product or ad is “following” them online. A third-party cookie for The New York Times might appear as an ad for an NYT Cooking subscription when browsing another website, such as AllRecipes.com.

The Four Types of Cookies

Cookies accomplish a variety of purposes. The four main types are listed below:

- Necessary: While most guidelines don’t require consumer consent for this beneficial cookie, it is best practice to explain what they are on your website. These cookies are critical to a user’s experience on a website. For example, the capability to hold your items in a virtual shopping cart as you browse is a necessary cookie for you to use an e-commerce site properly.

- Preferences: Also known as “functionality cookies,” these cookies give the website limited memory of your previous experience on the site, such as what language you prefer, your time zone, or your username and password.

- Statistics: These cookies track users anonymously to understand site functions better. For example, if you’re testing two similar website pages against each other, having statistics cookies would help you measure the views and interactions on each page regardless of the segmented audience. They can be incredibly helpful, especially as you put together your high-level content strategy.

- Marketing: These are almost always third-party cookies, and they track a user’s online activity to serve them more accurately targeted advertising. While marketing cookies can be incredibly useful for marketers, they are also the kind many federal regulations attempt to limit because of the loss of consumer privacy.

The Primary Types of Cookie Consent Banners

Clearly worded cookie consent messaging can help mitigate some of these consumer frustrations. Most businesses use four primary types of cookie consent banners on their websites.

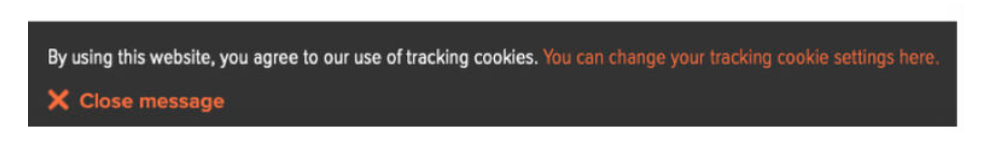

1. Notice-only consent and soft opt-in consent: In regions without strict regulations, businesses can use a simple “heads up” to tell the user that cookies are being used. There’s no “opt-in” or “opt-out” option here, meaning that this is not a recommended type of cookie consent for businesses that need to be compliant internationally. By continuing to more pages on the site after seeing the notice, the user opts into the business using cookies during their browsing experience.

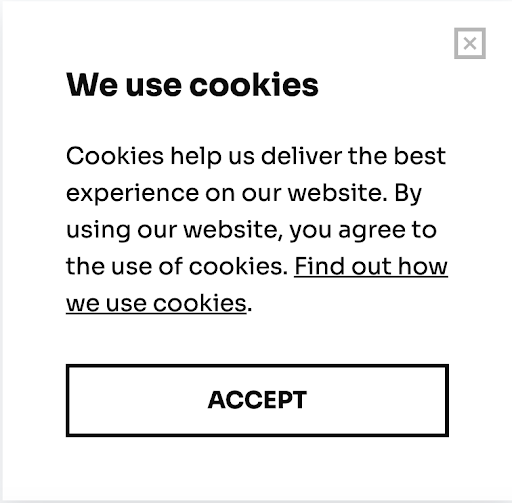

2. Implied consent: The prompt in this type of cookie consent banner is just “accept,” so it’s geared toward users automatically accepting simply because the opt-out button (hitting the “x” in the upper right-hand corner) is less obvious. This kind of cookie also commonly links to the cookie usage policy within that website, which should not be an automatic “opt-in.”

(Image Credit: Cookiebot)

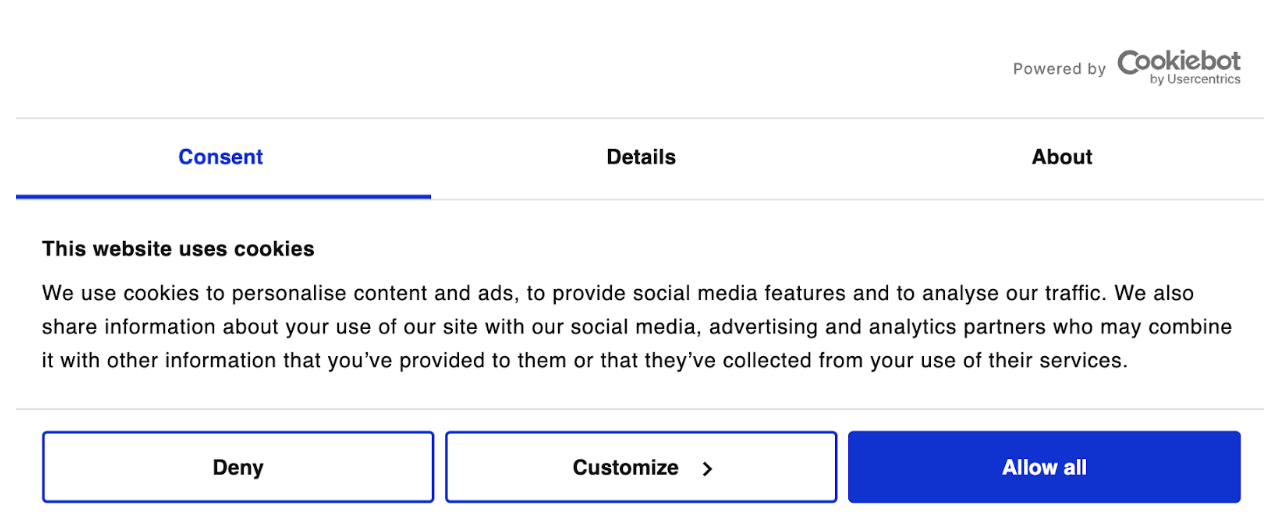

3. Explicit consent: This cookie consent type is becoming more common, especially for high-traffic sites focused on being GDPR-compliant. This model gives the user more than one option. The “customize” option is sometimes used to give site visitors the option to only opt into “necessary” cookies that are basic site functions, such as holding your items in a cart as you browse a clothing website. There’s typically also a “deny” button presented clearly on the banner.

This second option (below) is more direct than the first.

(Image Credit: European Data Protection Board)

This option is often the easiest for consumers to navigate because it gives them only two options, and one is to say no to all non-essential cookies.

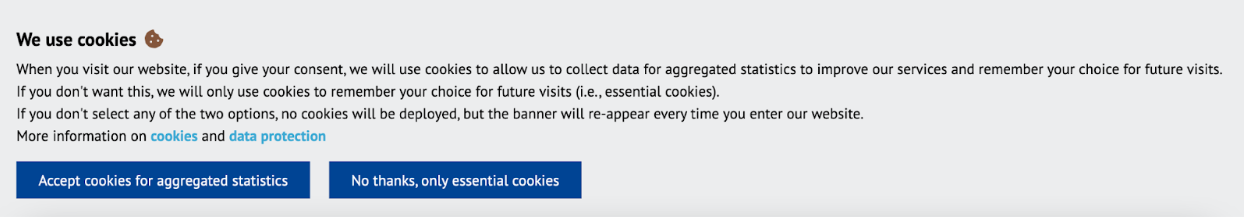

4. Comprehensive consent: This is the name we’re giving to cookie consent banners that give users a lot of information and options for their individual browsing experience. Below is a great example from McKinsey & Company. The initial pop-up allows consumers to either accept all cookies or go to “manage my preferences.”

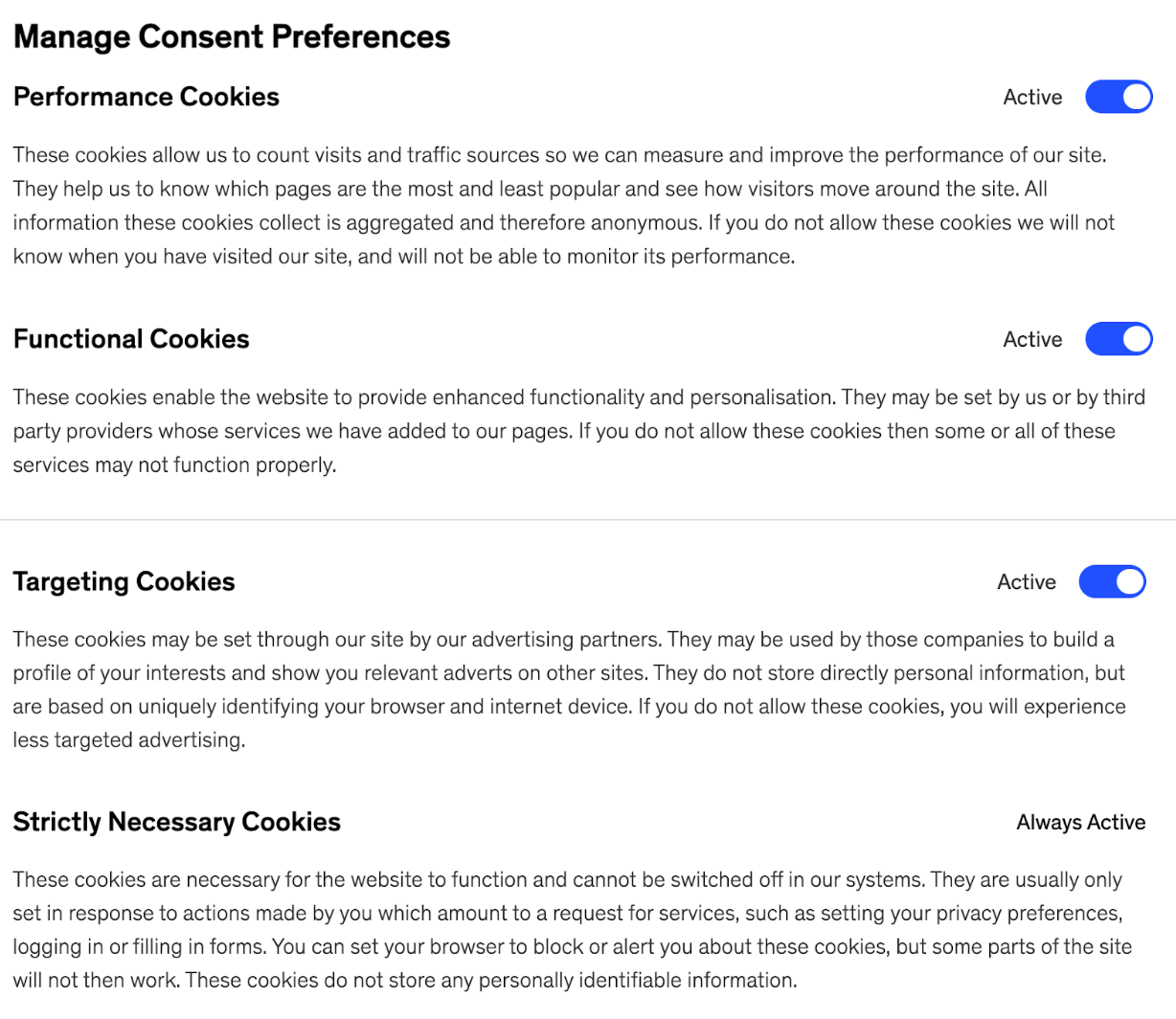

The “manage my preferences” option opens a new window:

This cookie consent alert divides the cookies into four types, three of which the user can opt out of. There is a clear explanation of why the “strictly necessary” cookies are always on, and the language explains why consumers cannot opt out of them without disabling part of the optimized browsing experience.

Using Cookie Consent Banners

The benefits of using cookie consent banners on your website include:

- A clear demonstration your site respects users’ right to data privacy

- No danger of having your website not comply with regional regulations, especially if your audience is international (or in California)

The main downside of using cookie consent banners on your website is that many consumers will opt out. Since the GDPR became law in Europe, roughly 50% of users opt out of cookies when they see the cookie consent banner on a website. This makes it nearly impossible to passively track users online or target those users who opt out with relevant content and ads.

Even if you’re not required to use them by federal or state regulations, consider using cookie consent banners to build trust with your audience. As long as you’re giving consumers the information they need about data privacy, you can make the language your own—making your cookie consent banners conversational and approachable can help reflect your company’s tone. Although this doesn’t directly impact your search engine optimization (SEO), it can underscore the trustworthiness of your company, encouraging visitors to browse as long as they want or need.

The Pros and Cons of Cookies

Consumers usually have a love/hate relationship with cookies. Although cookies that a user opts into can give the user a more functional, efficient web browsing experience, they can also make a user feel like they’re constantly being marketed to if the business using the cookies is mishandling them.

It can feel like the experience of moving to a new home and receiving a stack of promotional mail you don’t remember signing up for—it’s frustrating and a little unnerving that all these businesses know about your new home address.

The Benefits of Using Cookies

If you run a sock company and have a new yoga sock you want to run a marketing campaign for, you can build a target audience of people who have used your website to purchase an older version of the sock. You could even target people who have clicked on the page for that particular sock and then build out a segmented audience to target them with ads about the new sock.

This kind of passive tracking can help you build highly segmented audiences over time and track people’s behavior on your site—also giving you essential insight into your website’s (UX). Users who love your yoga socks will most likely not mind getting some advertising targeted to them—it serves as a reminder of a useful product they may want to purchase more of.

The Downsides of Using Cookies

Marketers have become notorious for using cookies to follow people around online with advertising, and that’s one of the main reasons cookies have such a bad name—overuse. If people become annoyed with your brand and don’t make many repeat visits to your website (or don’t stay on it for very long), it can hurt your brand’s trustworthiness and, by extension, your organic search potential.

The Growing Importance of First-Party Data

As marketers learn to grow and adjust to consumer expectations around privacy, it has forced them to get creative about engagement. Gathering first-party data (data that consumers voluntarily give you) is increasing in popularity.

There are many ways to engage consumers this way, including:

- Invest in high-quality content. Work with writers to build a newsletter or webinar series that users must sign up for. You’ll get their email addresses (be sure to use the appropriate opt-in box asking if people want to receive more than just the newsletter) and have the opportunity to serve them the requested content. By providing content that fits users’ needs, you build a long-term, trusting relationship with your consumers without relying on cookies. Learn more about working with a team of writers to achieve these results.

- Engage with people on social media. Brands that spend time and energy building content and personality on social media platforms make it easier for their fans to find them online. By hitting the “follow” button, these people opt to see your updates. And in most cases, you can also advertise to them directly through the platforms your brand is on. Social media marketing also allows you to promote giveaways, newsletters, and other email-based opt-in first-party data options.

Cookie consent laws impact passive marketing but allow businesses to think about new ways to engage their audiences more directly and personally.

What’s Next on Your Consumer Data Journey?

Ensuring your website is up to date with regulations and consumer expectations is key to having a strong online and offline brand presence. If you have relied exclusively on cookies to collect consumer data, consider bringing other marketing strategies into the mix—particularly ones that directly engage your audience and allow you to gather first-party data.

Want to learn more? Metric Marketing’s team of marketers has extensive experience with refining websites, managing marketing campaigns, and writing engaging content. Contact us today to get started.

Must-read articles

Looking for something else?

There's so much more

Ready to Inquire?